Counting Terrorism Charges and Prosecutions in Canada Part 2: Trends in Terrorism Charges

The Anti-Terrorism Act 2001 brought Part II.1 of the Criminal Code into being and with it, Canada’s terrorism offences. In the twenty years since that time, 62 individuals have been charged with terrorism offences by our counting (see Part 1 of 2, here). This blog post is not meant to be a comprehensive overview of the field. Instead, we set out merely to remind the reader of what constitutes a terrorism offence in Canada and then review some of the trends that we can see from the prosecuting and charging numbers to date. Let us begin with a very general reminder of how Canada’s Criminal Code terrorism regime works, before reviewing some of the interesting trends that we have seen to date.

Canada never did define terrorism and, as a result, has no generic offence for terrorism (or even terrorist activity). Rather, Canada spelled out a series of discrete offences between sections 83.02-83.04 and 83.18-83.23 of the Criminal Code, ranging from financing terrorist activity offences to participating in a terrorist group. All of these offences are predicated on proving one of two sub-units or predicates, those being “terrorist group” or “terrorist activity”. (The Code also lists a number of international terrorism conventions, the breach of which constitutes terrorist activity, and also defines terrorist activity itself as an offence, though how exactly those would be charged and prosecuted has not yet been clarified, as discussed in part 1 of this post.) Terrorist groups can be listed (as discussed here), or a group can be associated with terrorist activity at trial in order to prove terrorist group. Thus, the definition of terrorist activity is really central to Canada’s terrorism offences.

Terrorist activity is then defined as having three “predicates”, as I’ve call them in the past. These are: (1) that the action must be driven in whole or in part by an ideological, religious or political motive or clause (the “motive clause”); (2) that the action be committed with the intention to intimidate the public or a portion thereof, or cause a group (including the government) to do or refrain from doing an act (the “purpose clause”); and, (3) that the action causes death or serious bodily harm, risks lives, or causes serious risk to the health and safety of the public, and so on (the “consequence clause”). The reader may be surprised to learn that we do not know what precisely “ideological”, “religious” or “political” means for the purposes of this definition. In the result, we do not know with any degree of precision, as of writing, where an idea moves from being merely the driving force behind a “normal” crime and when that idea becomes an ideology for the purposes of the definition of terrorist activity. We should expect to see more refinement in the courts in the years to come, particularly with recent arrests of those with ideologies that cannot be tied directly to international terrorist organizations.

Perhaps a final reminder here is that there is understandable overlap between terrorism and hate—one might imagine most terroristic ideologies to be rather hateful when they lead to violence—but that is not necessarily so. A so-called “hate crime” (there is no generic hate crime in Canada, just as there is no generic terrorism crime) does not form the basis for the terrorism charge; rather, a terrorism offence forms the basis for the terrorism charge, and the basis of that offence will be an act done in association with a terrorist group, or an act that constitutes a terrorist activity, as defined above. Again, how exactly a “hateful ideology” fulfills the motive predicate of “terrorist activity” is neither completely clear, nor is it defined, but surely we can expect some overlap at least.

Terrorism by the Numbers: A group-centric offence no more?

Canada’s terrorism offences always contemplated the possibility of what Leah West and Craig Forcese have called “left of bang” offences (pre-emptive arrests before a violent action is taken) and “right of bang” offences (where the violent act has already taken place, e.g. an assault or murder). But in reality, the primary intention was to target inchoate crimes (left of bang), such that terrorism could be disrupted and prosecuted before any damage had occurred. The Criminal Code also contemplates both offences for members of a terrorist group and, in theory, offences that could be used against so-called lone wolves. But again, in practice it has been much easier to charge individuals left of bang when they are a member of a group; cases involving right of bang lone wolves have been much clunkier and the applicable terrorism offences are not always as clear (see for example R v. Ali).

Looking at the numbers, it is then perhaps no surprise to see that 59 of the 62 individuals charged to date can be associated with al-Qaida or ISIS inspired terrorism—offences where the individuals are either part of their own group of conspirators “inspired” by international groups (for example the so-called Toronto 18) or where the perpetrator claims direct affiliation with a relatively stable and well understood international group such as ISIS. The remaining three cases include terrorist financing charges against an individual associated with the listed LTTE, and two cases in the past year, one involving an accused said to be motivated by the Incel (Involuntary Celebate) ideology, and the other being Nathaniel Veltman, accused of killing four family members and attempting to kill another (a child of just 9) in London, Ontario.

These latter two cases signal a potentially significant shift in the Canadian landscape for a variety of reasons. First, they are both “right of bang” situations and together with R v. Akhtar are the first three—all charged within the past year or so, as of this writing—where the accused are charged with murder—terrorist activity (section 231(6.01) of the Criminal Code). As such, these two cases may also represent a shift away from what seemed to be the tradition of treating “left of bang” as terrorism, but not necessarily “right of bang” activities that certain appear to be terrorism (think here of the lack of terrorism charges against the Quebec Mosque shooter, Alexandre Bissonnette). Second, these cases are the only two—and, again, both in the past year—that target what might be called far right ideologies (depending on how one classifies “Incel”), signalling that a wider range of groups and ideologies will be considered for terrorism charges going forward. This is a welcome development, at least in terms of ensuring consistency across how different ideologies with the same dangerous and hateful actions are treated. Third, Canada’s initial foray into terrorism prosecutions involved individuals both in groups and associated with particular international terrorist organizations: from Khawaja who was said to be al-Qaida inspired along with his group of likeminded conspirators (arrested in England), to the Toronto 18, to the Via Rail plotters. Today, we are seeing actors that do not seem to have a broader group and if they are associated with an international terrorist group, it is not clear how directly or how fully they are in agreement with or acting “on behalf of” just one such group. The result is that our laws will be tested in the coming years in terms of how we can successfully charge and prosecute lone actors, those without a close connection to a single broader group from which to draw ideas about their intentions and motivations, and how new and different groups—Incels, or newly formed far right groups—can be similarly associated with terrorist activity.

How are we doing? Conviction Rate for Terrorism Charges Between 2001-2021

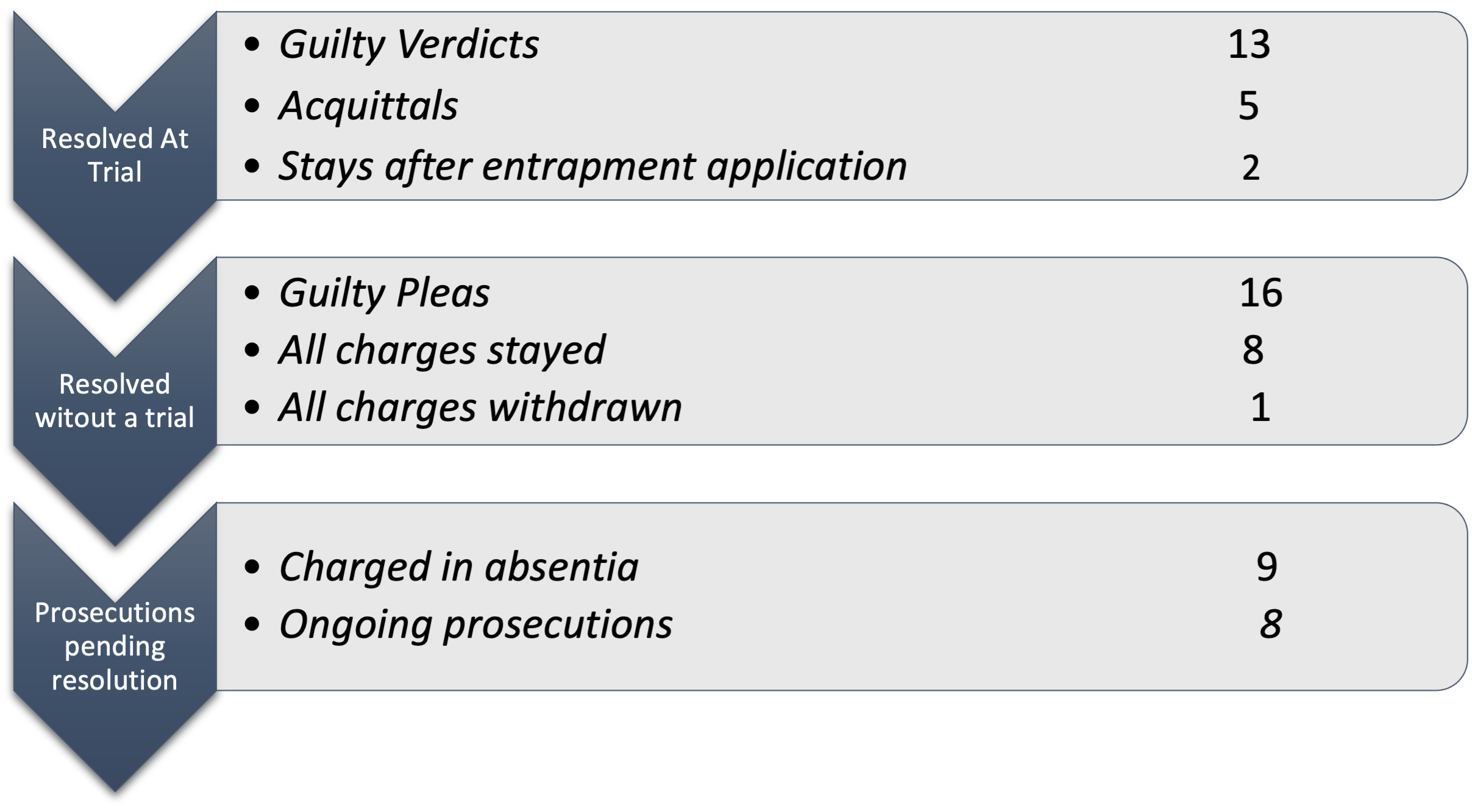

While 62 individuals have been charged with terrorism offences, many of them will never see trial, for example if they are presumed deceased having travelled overseas to fight. As a result, we currently have 45 individuals that have gone to court as well as 8 further cases in progress.

These numbers indicate that 29 out of the 45 resolved terrorism prosecutions resulted in a guilty plea or a guilty verdict at trial; put another way, approximately 64% of accused tried to date have been found guilty.

This rate might seem low to the casual observer, but it is comparable to (and slightly higher than) the percentage of cases that ended in guilty verdicts or guilty pleas across all adult criminal court cases in recent years, which is 63% percent. The rate of stays and withdrawn charges in terrorism prosecutions is approximately 24%, a slightly lower rate than across all criminal cases (32%). However, 11% of terrorism prosecutions resulted in acquittals, over twice that across all criminal cases (4%).

Add it all up and we convict at a rate that one would expect, but withdraw fewer charges and acquit at a higher rate than might be expected if generalizing from the broader criminal justice system. Such numbers should not be surprising: we likely withdraw less because of the seriousness of the terrorism charges and the fact that once they are charged, the Crown is committed to the prosecution having been required to get the Attorney General (in practice the Director of Public Prosecutions) to sign off. At the same time, these are extremely complex trials, often involving inchoate offences (planning to do a future act that may or may not ever come to pass) with complex proofs of motive and affiliation required that is not the norm in our criminal justice system. Thus, there is not an easy answer to the question of whether Canada is doing “well” in terrorism prosecutions, but the numbers do not suggest, on first blush, anything terribly unexpected or about which we should be worried. That is to say, while there is certainly disclosure, intelligence to evidence, and investigative complexities associated with prosecuting terrorism (and indeed national security offences more broadly), the big picture suggests we are not “bad” at prosecuting terrorism (once at trial) or unable to secure a conviction; indeed, we are doing about how we usually do in criminal trials.

Overall, it might be better to say that despite some serious procedural issues related to disclosure and presenting evidence at court, which definitely require addressing, we can still be comfortable with the fact that the conviction rate is right where one would expect. We secure convictions much more often than one sees acquittals, and (rightly) the system is balanced enough such that a terrorism charge does not lead inexorably to a finding of guilt. (Recall that success in criminal law is not about convictions, but about seeing a fair system that provides justice that flows from reliable evidence; this includes both convictions where warranted and equally acquittals where justified under the rule of law. While an extremely low conviction rate would be concerning, one also does not want to see any crimes, but particularly thought-and-politics tinged terrorism trials, as automatic convictions.)

Having said all of this, there seems to be a (possible) lesson in here for defence lawyers in terms of how they approach trials—and perhaps in turn for judges and prosecutions. In recent years, 59% of accused across all criminal cases in Canada pled guilty and only 9% of prosecutions proceeded to trial. However, 35% of terrorism prosecutions ended in a guilty plea while 44% of terrorism prosecutions proceeded to trial. Put it all together and we see that terrorism prosecutions have comparatively fewer guilty pleas and significantly more trials.

There are a variety of possible explanations, including cases that are more likely to proceed to trial where they are procedurally complex, where terrorism charges are often associated with inchoate acts (those that have not taken place) and thus can be more subject to evidentiary and procedural wrangling and disputes about what was actually intended or likely to come to pass. But it is also notably that all 29 individuals found guilty were sentenced to various lengthy periods of incarceration, with some research suggesting there is seemingly little to no discount for guilty pleas. Put another way, the usual incentive to plead guilty—that it would come with a reduced sentence—does not seem to have been present in terrorism trials. Given that the acquittal rate at trial is also slightly higher for terrorism offences and that there is more procedural wrangling around intelligence to evidence and disclosure—in particular associated with source and national security privilege—it is perhaps no surprise that more cases are going to trial. Accused (and defence lawyers) would seem to simply have less incentive to plead guilty, at least on our history thus far. Of course, going to trial and securing a just outcome based on a fair trial is to be encouraged; but considering terrorism trials are already complicated and expensive, this tendency is costing the taxpayer a fair penny and may be costing accused years of uncertainty and longer terms of incarceration. So, while defence lawyers may wish to take heed, judges and prosecutors may also wish to consider the message being sent with sentencing to date and particularly how guilty pleas are negotiated.

Gender & Terrorism Prosecutions in Canada

In looking at the individuals charged with terrorism in Canada it is striking the extent to which it is male dominated. Indeed, that initial impression is borne out by the numbers: the percentage of male accused in terrorism cases (92%) is significantly higher than the Canadian average across criminal offences (closer to 80%).

Even as compared to other serious, violent offences, terrorism skews predominantly more male than its comparators: approximately 86% of homicides are committed by men and 89% of both attempted murder and robbery. At the same time, Jessica Davis’ work has suggested that one would expect to see something approaching 23% female involvement or higher in terrorism (see here). We are thus left with a conundrum: either terrorism offenders in Canada over the past twenty years have skewed surprisingly male by chance (our numbers remain fairly small overall) or because of something unique and as of yet unidentified about the ecosystem; or, women are equally involved in terrorism in Canada as we have seen internationally, but they are not being charged as such. The conundrum demands further study and could have serious implications. For example, is it that police have not taken the role played by women in terrorism seriously in terms of charging Canadian suspects? Is it that the role itself is more clandestine and requires different investigative techniques? Is there bias at play here, whereby the danger posed by women is downplayed? Is there something socio-criminological at play that is causing a disproportionate number of men to get involved in Canada? The repercussions for responding to ideologically motivated violent extremism, investigating it, and charging/prosecuting it, could be significant.

Terrorism and Prior Criminal Records: Maybe not the ‘normal’ perpetrator?

The recent (June, 2021) arrest and charging of Nathaniel Veltman in London, Ontario revealed, to the close observer, another unusual aspect of terrorism offences and perpetrators in Canada: most people do not jump straight to very violent, serious offences, but rather start smaller; indeed, a recent Canadian study found that 69% of accused had a prior criminal record. This is simply not true of terrorism to date in Canada, where only 11% of accused had a prior criminal record.

This suggests several difficulties for investigators. For example, if almost 90% of those charged with terrorism have no criminal record, then they are less likely to be on the police radar and less likely to have come into contact with the system—for good and bad—in the past.